Someone once described drama as real life with all the boring bits cut out. This is generally true, but anybody who’s taken a good, long look at their life will tell you that often the boring bits are as interesting as any of the conventionally classified highlights. Such is the case in Michael Winterbottom’s Genova, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

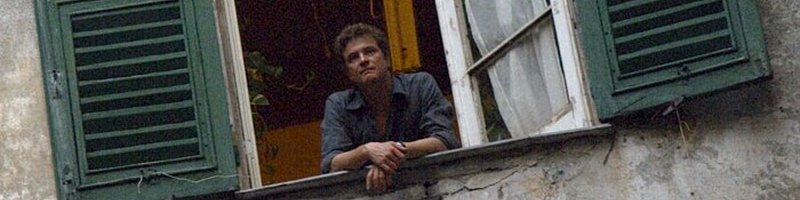

The plot sets itself up in the traditional way family dramas do: a cheerful drive home ends in a fatal accident, leaving Kelly (Willa Holland) and Mary (Perla Haney-Jardine) motherless, and their father Joe (Colin Firth) with the uneasy prospect of single parenthood. Five months later he takes the kids to Italy, to Genoa (the film uses the Italian spelling of the city), to start a new life in a new place.

While he settles into his lecturer job at a university with the aid of old college friend Barbara (Catherine Keener), the girls begin to cope with their new surroundings. They spend their days at piano lessons and lounging on the beach, drinking in the strangeness of the ancient city. Kelly immerses herself in nights on the town partying with new friends, trying to have some semblance of a normal teenager’s life. Mary, meanwhile, begins to see ghostly visions of her dead mother (Hope Davis) on the walk home through narrow, twisting lanes.

Or at least, that’s what it seems like to us, the seasoned movie-goer. It’s never strictly defined as a paranomal visitation or merely psychological trauma that makes the young girl see the departed parent.

It’s obvious that Winterbottom is keenly aware of this, and the film deftly — perhaps annoyingly to some — does a tightrope walk between the normal and paranormal. There are no cheap scares or macabre demons, but on the other hand the film is littered with subtle otherworldly iconography and unsettling background music. And then it throws in what can only be described as standard melodrama tropes every now and then. It’s almost as if the director is daring us to consider this a paranormal thriller, but also playing with our preconceived notions using the language of ghost movies & melodramas.

This misdirection is perhaps the only criticism of Genova I have, because if you aren’t waiting with bated breath for monsters to pop up, it’s one hell of a film. It perfectly captures the starkness and lack of drama in the months following the loss of a loved one. This isn’t a picture postcard film of beautiful ancient cityscapes and swelling ethnic music as people dramatically move on with their lives, nor is it a gritty tale of the dangers of strange cities and the bleakness of bereavement.

The term ‘documentary-like’ is very easily bandied about for films that do not dress up their locations or actors in a very formal, staged way, but that doesn’t really do justice to this. Genova is undeniably cinematic. The digital camera work by Marcel Zyskind brings the same level of immersion and verisimilitude that I mentioned in my Public Enemies review — it’s a beautiful film to look at.

The city of Genoa seeps into every frame, almost spilling into the theatre’s aisles, and becomes a character in itself. It ceases to be background, without ever strutting to the fore of the stage and doing a song and dance. The characters negotiate this labyrinthine city not in touristic jaunts and peppy montages, but in quiet wonder. Rarely have I seen a film that conveys the feeling of being in a new city — that undercurrent of trepidation, that inability to do anything else but absorb — quite as well.

There are many other films you can look to for good supernatural chills. There are films that paint prettier (or grittier) pictures of exotic locales and their quirks and wonders. But in the economy of its script, the immediacy of its digital cinematography, the considerable talent of its actors and the sheer normalcy of events that befall their characters, Genova paints an arresting portrait — one that is not soon forgotten.